Our first two letters examined the history of radical gay and lesbian printing and publication in Iowa City and Grinnell during the 1970s. Moving away from this historical time period, our next few letters take a biographical approach to share the lives of LGBTQ Iowans from across the state. What better way to start this short series than with a letter featuring Iowa’s most famed artist, Grant Wood.

Remembered for is 1930 painting, American Gothic, Grant Wood spent his career promoting Regionalism, and artistic movement purely American in form. Wood, of course, was focused on the region of the Midwest. Born on a farm just south of Anamosa, IA Wood spent his childhood in the idyllic farmland landscape of the region until the age of 10. Following the death of his father, Maryville Wood, he and his family moved to Cedar Rapids. It was in the city that Wood’s creative side flourished. Away from the masculinity shaped by farm life and Quaker ideals, Wood was able to pursue a career as an artist.1

Wood served as a soldier during World War I but never saw any time abroad due to appendicitis. Yet by sketching soldiers, Wood was able to hone his skills and launch into life as an aspiring artist. It was art, not war, that brought Wood to Europe four separate times throughout the 1920s. A trip to Europe was essential for American artists in the early 20th Century as training was seen as crucial due to the lack of an artistic style that was birthed out of the United States. After his final trip to Europe in 1928 to oversee the fabrication of a stained-glass window in Munich, Wood returned to Cedar Rapids to develop a uniquely American style of art.3

This quest no only led to Wood’s iconic style throughout portraits and landscapes that capture life in Iowa and the Midwest, it led to the founding of the Stone City Art Colony and School in the summer of 1952. Wood found himself back outside of Anamosa in the tiny village of Stone City. The fame and clout Wood acquired from American Gothic afforded him the ability to co-found and lead the artist colony. A commitment to Regionalism and Wood’s quest for an authentic American artistic style took center stage at the Stone Colony.

More importantly, as historian Christopher Hommerding argues, Stone City provided Wood the freedom from heteronormative institutions to live queerly. At least for two summers. This is not to say the art colony was an explicitly queer space, it afforded Wood both the privacy and distance from family and city life in Cedar Rapids. Notably, Wood resided in an ice wagon hauled from Cedar Rapids to the art colony and shared the tight quarters. For the first summer Wood shared his wagon with John Bloom, the groundskeeper for the colony. For the second summer he shared with Charles Keeler, an artist from California. Newspaper reporters from across Iowa consistently spoke in euphemisms when discussing the colony, leaving the possibility of same sex relationships that were open secrets.4

After the summer of 1933, the Stone City Art Colony closed due to accumulated debts and Wood’s acceptance of a new job. Wood served as director of Iowa’s Public Works of Art Project at Iowa State College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts in Ames (presently known as Iowa State University). For the fall of 1934 Wood accepted a lecturer position at the University of Iowa in the Department of Graphic and Plastic Arts and moved to Iowa City. In March of 1935 Wood surprised many and got married to singer and actress Sara Sherman Maxon. An unhappy marriage led to divorce in 1939.5

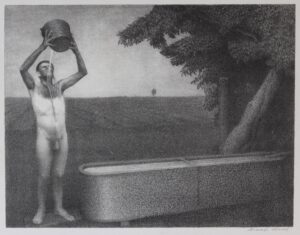

That same year Wood created a lithograph of a male farmhand drinking water in the nude for the Associated American Artists titled Sultry Night. Meant for low cost distribution to the public, the print was banned by the post office for being pornographic and obscene. Wood defended his art work as one culled from his innocent, rural childhood. Yet he defaced the painted version of the image by sawing off the man in the nude. This forced erasure is seen by numerous Wood scholars as an act of self-censorship mandated by society for his homosexual desires.6

That same year Wood created a lithograph of a male farmhand drinking water in the nude for the Associated American Artists titled Sultry Night. Meant for low cost distribution to the public, the print was banned by the post office for being pornographic and obscene. Wood defended his art work as one culled from his innocent, rural childhood. Yet he defaced the painted version of the image by sawing off the man in the nude. This forced erasure is seen by numerous Wood scholars as an act of self-censorship mandated by society for his homosexual desires.6

Wood also faced scrutiny in his academic life at the University of Iowa after art historian Lester Longman joined the art department as chair in 1936. The clash and controversy between Wood and Longman pertained to art and Longman’s devaluation of Wood’s artistic technique and the Regionalist movement. The University was trying to keep Wood, their most famed professor on staff, denying his attempt to resign and offering him a sabbatical for the 1940-1941 academic year instead.

Longman took the absence of Wood to discredit him as an unskilled artist in professional circles and at the university. It was in this moment that Longman attempted to smear Wood’s reputation due to his “personal persuasions” and accused Wood of homosexuality in a meeting with University President, Virgil Hancher. The University dealt with the turmoil between both men by moving Grant Wood into the Fine Arts under a new supervisor and into a new studio.

Upon Wood’s return to teaching in the fall of 1941, the artist discovered he had pancreatic cancer that October. He died on the night before his 51st birthday, February 12th, 1942. Longman’s continued attacks on his art and character after his death led to Wood fading from the University’s memory until the 2010s and a renewed interest in scholarship on Wood.7 Yet Wood has long been remembered in Anamosa, Stone City, Cedar Rapids, and Eldon where Wood painted American Gothic’s house.

It wasn’t until 2010 that Wood’s sexuality was taken seriously with the publication of R. Tripp Evan’s biography Grant Wood: A Life. As scholar Sue Taylor articulates Wood masqueraded as a rural, Midwestern farmer turned artist. His iconic overalls became a cloak to veil his sexuality in a heterosexual masculine facade.8 It is a complex task for historians to label someone’s sexuality with terms they either never used, denied, or even had. Yet scholars of Wood agree that his same sex desires and repression emerge throughout his art and acknowledge that his sexuality was at best an open secret. Whether labeled gay or queer it is clear that Grant Wood’s legacy in Iowa is much larger than American Gothic and the Stone City Art Colony and School.

Grant Wood’s life gives evidence of queer Iowan existence across the first half of the 20th Century. He demonstrated that in the face of censorship and personal attacks there were still moments and places where the queer pastoral life in Iowa could exist and survive.

In solidarity and love

Notes

- Barbara Haskell, Grant Wood: American Gothic and Other Fables (New York: Whitney Museum of Art, 2018), 13-14.

- Christopher Hommerding, “As Gay as Any Gypsy Caravan: Grant Wood and the Queer Pastoral at the Stone City Art Colony,” The Annals of Iowa 74, no. 4 (2015): 391.

- Anya Ventura, “Sultry Night: Grant Wood’s Queer Midwest,” LA Review of Books June 10, 2018, https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/sultry-night-grant-woods-queer-midwest.

- Hommerding, “As Gay as Any Gypsy Caravan,” 384, 388-389; R. Tripp Evans, Grant Wood: A Life (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2010), 151-152.

- Hommerding, “As Gay as Any Gypsy Caravan,” 407

- Ventura, “Sultry Night;” Sue Taylor, Grant Wood’s Secrets (Newark, DE: University of Deleware Press, 2020), 89-90.

- Joni L. Kinsey, “Cultivating Iowa: An Introduction to Grant Wood,” in Grant Wood’s Studio: Birthplace of American Gothic (Cedar Rapids, IA: Cedar Rapids Museum of Art, 2005), 27, 29, 31.

- Taylor, Grant Wood’s Secrets, 4.

One Reply to “History-By-Letter #3 | Grant Wood”

Comments are closed.